- Meant For you

- Posts

- The Mortifying Ordeal of Being Published

The Mortifying Ordeal of Being Published

Eleven writers weigh in. Plus, my book's sales: exposed!

Today is the one year anniversary of An Honest Woman’s release which means it’s finally available in paperback. You can procure your very own copy, in hard or soft cover, or—what the hell—both. This is not the first book I’ve loosed into the world but it was my first with a so-called Big Five publisher and that process, as you might suspect, felt very different from self-publishing. Below, I go into detail about how and why I found it challenging, and share sales numbers since if you’re even half as nosey as I am, you want to know. It’s long, but I hope entirely of interest. If some part of it isn’t, you know how to scroll. (I hope???)

I also asked ten other authors, all of whom have published two books or more, about their experiences with this weird rite of passage, and was humbled by the generosity and candor of their replies. I’ll be thinking about what they shared for a long time. You can jump to any of their takes by clicking their names, which I’m listing in order of reply-reception: Lydia Kiesling, Mattie Lubchansky, Anonymous, Jaya Saxena, Rumaan Alam, Daniel Lavery, Larissa Pham, Andrew Martin, Katie Heaney and Isle McElroy. (This won’t work with all email clients but should work on any browser.) Thank you, fellow writers. I hope you each enjoy the Charlotte Shane bump (of book sales? No, better—of appreciation and friendship.)1

On to my reflections….

Bees kept flying around while I took this picture but sadly they were all camera shy.

On numbers: As of this morning, my author portal says 12,863 books have sold, only 3,417 of which are physical copies though this data is attributed to BookScan which I’ve heard skews low. When I asked my editor Carina if this is true, she said, “bookscan numbers can indeed be lower, but I do think that people tend to exaggerate by how much. It’s usually not a big discrepancy. There’s a bigger difference when a book has done really well in ‘special markets’ like museums or stores like Urban Outfitters or other non-book focused retailers that don’t report into bookscan. But the number of retailers like that that continue to sell books is diminishing every day.”

This is my second time looking at these estimates. The first was in January I think, or at least many months after the book’s release, and the total was around 7,000. Then as now, most of the sales are audiobooks, which shocks me because I don’t listen to them and kind of forget they exist. I wish I’d been given the opportunity to narrate mine, but maybe it’s for the best that I didn’t and this isn’t something I dwell on anyway. (To reiterate, I routinely forget that audiobooks, including mine, exist.)

I have no idea how this number lands for those of you reading, but it feels good to me. It’s hard to sell a lot of books and even 1,000 is a lot, especially when you imagine each book going to individual strangers in the first year of its release. (I’m picturing a line of people now, with COVID-precaution style spacing, and my book is flying into their hands. That’s crazy! It’s a long line!) This “first year of release” aspect, I think, should not be overlooked. I read more books than most people and the vast majority of what I read wasn’t released this year or even in the past five or ten. Buying and reading a book that’s hot off the presses isn’t a habit of mine nor of my writing peers, frankly, in part because we get galleys. But I’m very grateful that this is routine for other people. Especially the audiobook listeners—love you guys. Shout out also to libraries.

For context, the information publicly available about current book sales suggests most (more than 65%, according to a data set from 2022) do not sell a thousand, let alone tens or hundreds of thousands. In 2023, Esquire quoted Dan Sinykin as saying, “Somewhere between 2% and 12% of books, as of today, sell 5,000 copies.” (Books excluded from this range sell less.3) Last year, in a big piece for Slate about book statistics on the whole, Lincoln Michel wrote:

“Someone from a prestige Big 5 imprint whose books are often award contenders and bestsellers once told me any book that sold fewer than 25,000 in print was a failure for the publisher. On the other hand, many literary fiction writers have told me that anything more than 5,000 sales is a success. So, some small-press editors might be happy with 1,000 sales.”

Speaking as a small press editor/publisher, they are indeed. Through TigerBee, I’ve sold about 1500 N.B. and 3500 Prostitute Laundry, all of which were paperbacks2 and most of which were sold online—but these titles have been out for ten years (!) These numbers, too, are perfectly respectable to me given how modest/nonexistent their coverage and distribution. Also, it would be kinda bananas to process 10,000 books through my home, which happens to have an excess of stairs, and would necessitate many trips to the Post Office. (But I am willing to do it. Please don’t hold yourself back from purchasing thousands of copies of Prostitute Laundry on my account.)

On books in the physical world: As I recall, I was always pretty pleased with my self-publishing experience, but that feels doubly true now that I have experienced being published by others.4 Self-publishing gave me education and insights I would not otherwise have, and connected me to people and projects I’d otherwise not connect with, but it didn’t just provide me with a bunch of good experiences, it saved me from bad ones that hadn’t even occurred to me as possibilities.

I think it’s normal, for instance, for an author to go into a bookstore and hope to see their book there, ideally displayed prominently. But unless you’re Emily Henry or Michelle Obama, this is easier dreamed of than done. As Arianna Rebolini wrote in a candid post about her new book, “I've stopped looking for it in bookstores because it became too depressing to go in hopeful and leave embarrassed.” Sometimes I think it feels nicer to see a picture of one of my books in a bookstore (unread! unsold!) than it does to see a picture of it in someone’s hand or home, which only makes sense through the lens of wanting my books to be public entities, i.e. part of the culture, or at least, part of a culture. It’s the same reason I craved being reviewed while knowing that reviews don’t sell books; I want the book to be worthy of commentary and conversation.7

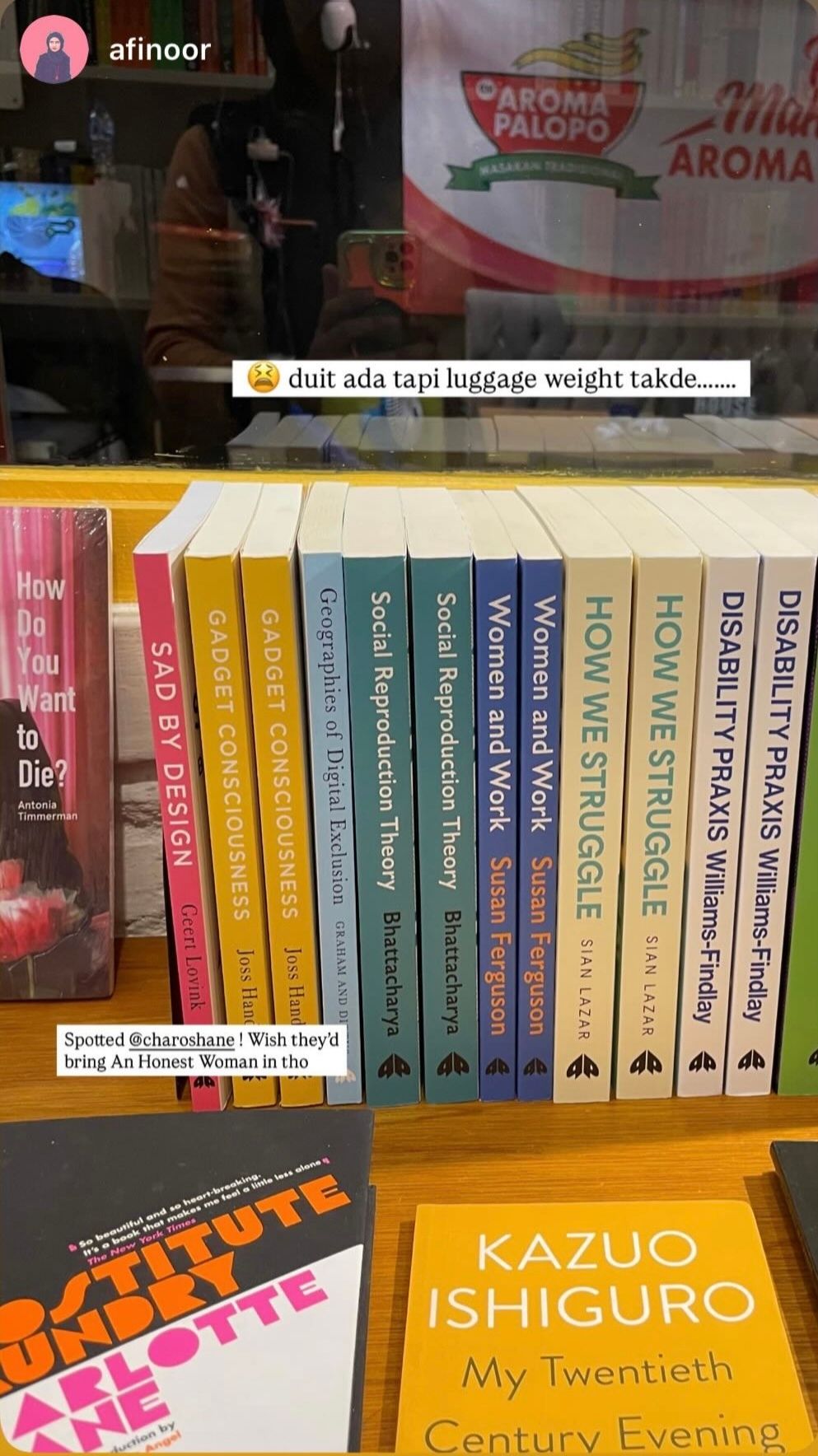

Prostitute Laundry (Serpent’s Tail edition) on sale in Jakarta! Thank you, @afinoor ❤️

When TigerBee books came out pre-pandemic, we got them stocked at a bunch of bookstores in Manhattan and Brooklyn, and we (Sam and I) would hand deliver them and chat with the booksellers. It was so friendly and authentic-feeling, and those relationships usually manifested in our books receiving prime placement. It was marvelous to go into Book Culture or Bluestockings or Spoonbill5 and see N.B. and Prostitute Laundry face out at the register or face up on front tables. Especially on the Strand’s capacious and busy first floor, the sight delivered me into a state of interiority that I can only liken to that of crying alone in public: a sense of simultaneous smallness and bigness, invisibility and presence. I haven’t felt the need to seek that out with An Honest Woman, probably because I was conscientiously trying not to invent scenarios for disappointment, but also because I’d had the experience before.

It seems widely known by now that book tours are expensive and rarely pay for themselves, let alone turn a profit. But the nice thing about a tour, besides it being professionally validating, is that you end up in establishments that are selling and, importantly, displaying your book. That’s a big ego boost—until the event is not as well-attended as you’d hoped. (Though I kind of love smaller groups because I like to feel as if I’m actually talking to people vs. holding forth.)6

On validation: The theme here is that I had a lot of control when I was self-publishing so my expectations were largely in line with reality. When a big publisher is involved, a wider variety of success and affirmation felt possible no matter how unlikely. Translation rights! Movie/TV rights! Celebrities posting your book to their grid! I didn’t expect to be nominated for awards or selected for a famous book club or anything splashy like that. An Honest Woman is, after all, a short memoir about love, sex, and getting paid for it. Yet I expected something to happen after it was published…and nothing really did. The best expression of this that I’ve found is from a newsletter by Laura Leffler, who repurposed a meme that I in turn will repurpose here:

This is the weirdest disappointment to try to explain because, on inspection, it’s wholly irrational. The desires are so inchoate, inarticulable. Even after a lot of hope management, avoiding Goodreads and Amazon ratings and reviews, and generally trying to adhere to best practices when it came to not hurting my own feelings, I felt like a flop for months after my book came out. This was complicated by the fact that it’s personal nonfiction, and by my status as (former…? current….? Bueller….?) sex worker. I don’t want to belabor that right now and I’m sure you don’t want me to either.

As best as I can tell, I thought An Honest Woman would render me validated or accepted in some marked, lasting way, as a writer of course but also I guess as a person…and the human condition is, rather famously, that nothing external makes you feel this way. And so nothing is ever enough. It’s why Pulitzer winners can nurse grudges about not winning a Nobel, and why the biggest, most bankable bestsellers in the world can nurse grudges about not being critically lauded. Don’t these sound like horrible fates? Thank God they’re avoidable i.e. voluntary.

For me, time was a miracle worker. I went from feeling shitty and bitter to totally at peace with and even pleased by my book’s trajectory thus far, and most of that came simply from getting distance, letting the freshest emotions cool down and considering things from a new perspective, a perspective afforded by temporal distance. The whole process brought me to a number of realizations about myself and my aspirations that I now lean upon heavily, and I’m sure I’ll write more about them later this year. One last thing: I believe my publisher, Simon & Schuster, handled my book in a canny, competent, supportive way, which (from what I hear) is rarer than it should be.8 So, credit where it is due.

Ok, that’s plenty from me. Here’s everyone else!

Lydia

I have published two novels. After the first one I was in a horrible state but I didn't make the connection between my horrible state and the possibility of a kind of postpartum slump after a book's publication. It was 8 years ago so it's not crystal clear, but I remember feeling both low and sluggish while also being wildly agitated and anxious. I had two kids under three and couldn't afford to live where we lived and right after publication my husband's dad died, so there were plenty of reasons to be anxious and sad, but I remember attaching the anxiety to the idea that I had to somehow complete a partial book proposal and try to sell it as soon as I possibly could. I knew this was a thing other people had done but I was in retrospect willfully misunderstanding that it's really only an option for people whose books are doing incredibly well. My first book had some great things happen for it but it wasn't a big success relative to the amount of money I was paid for it (which was a huge privilege already, etc. etc.). So I kept churning out twenty pages of bullshit and would bring it to my agent like a cat with a dead lizard until she finally gently told me "write a whole draft of a book and then show me." The bullshit I was churning did eventually become my next book, but it took a lot of research and thinking and slowness for that to actually happen. Which in retrospect was really only four years. But that feels like an eternity when you have a sense that you only get this one shot for your career as a writer to happen, not to mention get paid. It wasn't until more than a year after I published the first book that I understood how fucked I had felt during that time period and how much of it probably had to do with the insane months-long anticipation of the pre-pub period (not to mention the scramble of the editorial process), the few days of adrenaline around publication, and then the nothingness of a few weeks after publication (combined with that agitation to get yourself back on the train through selling another book).

By the time I was publishing my second book I had been through the peak Covid era with the aforementioned small children, and I felt like I had lived ten years in the five years since my first book had come out. I had also started therapy and finally was dealing with some of my lifelong anxiety and sense of doom etc. I felt beleaguered but also just so happy that I had been able to finish and sell the second book (for 25% less money than the first one, but that was okay!). And I had a strong sense that ultimately how the book "did" was out of my hands, because everything is out of our fucking hands (again, Covid era). I made an effort to promote it but I did not destroy my mental health to try and pump out essays to support its publication, etc. I expected to feel depressed when it was over. And I did end up feeling incredibly depressed, not because of the book, which came out in August 2023, but because a few months later October 7 happened and it felt like the world went insane and suddenly I felt like my job was to be someone who was saying Free Palestine while so many people in my orbit were not. And that changed the trajectory of the next year in terms of my activities and energies, and that distracted me a lot from the book and its performance, and it also frankly made me regret going with an imprint whose "brand" was politics that I had found suspect before but had talked myself into based on some of the other media they had acquired, but that I now found enraging. I also went on Wellbutrin, which is something I should have done years ago but was always afraid it would hurt my creativity. Which is stupid, but also something I worry has actually happened. Then I remember that feeling like you are in this weird ideological cold war with the culture you live in can also numb you out and make it hard to think. Not for a lot of people who have produced amazing work during and about this time. But for me. I'm still trying to figure out how to get it back. There are no lessons here other than that the things that happen for your book are not because your book are good or bad or because of things you did or didn't do. And that this career is batshit and very hard. If you write a book just try to be so proud that you did that because most people can't and that's why they are using AI to read and write books. But balance that pride with the understanding that no one is obligated to care, so anyone caring at all is a gift.

Lydia Kiesling is the author of The Golden State (Picador 2019) and Mobility (Crooked Media Reads 2023).

Mattie

Auspicious to receive this [ed: my email asking for contributions] the literal day (!) my new book comes out. I can either count it as "my third book" or "my eighth book" depending on your criteria, but I think truly it's "my second book" because it's my second full-length, solo GN. Anyway! It's weirdly the Same – I'm just staring at my computer screen for some sort of feedback like a woman pacing her widow's walk in 19th-century Rhode Island. But it's also Worse – I thought I was prepared emotionally this time, but alas! No dice. I'm sort of a wreck to be honest, but I don't know if that's the difference in the media landscape this one is coming out during, and the content of this book (If I could do it again I'd put out the book full of nude transsexuals and cop murder back when Woke was around. But hey, c'est la vie) OR if it's something else more broken about me in the interim. Certainly this book is more important to me, I think it's my best work, so I'm quite nervous! But it's also Better – I know that my life is not about to change in any significant way. This is just what my job looks like for a couple weeks. You know, you can be completely bugnuts insane at work and it's totally fine!

[Addition] doing events /going on tour remains the exact same kind of stressful, it feels like it’s a party for a medium-big birthday every single night for like two weeks. Who’s coming? Is everyone here? See you there?????

Mattie Lubchansky is the author of Simplicity (Pantheon 2025), Boys Weekend (Pantheon 2023), and The Antifa Super-Soldier Cookbook (Silver Sprocket 2021).

Secret Friend

in my experience it does not get better but one does become more resigned and cynical which... i guess... makes it easier? don't put my name on that though please as i am currently doing battle with my editor over a book that is supposed to come out next year and THIS BOOK, SURELY will be the one that CHANGES EVERYTHING FOR THE BETTER, once i just get my EDITOR to see how BRIGHTLY my LIGHT SHINES

Secret Friend is the author of four books.

Jaya

My last book came out on December 29, 2020, which I think is a Top 5 absolute worst date for a book to come out. I spent much of the lead up not only dealing with the mental drain of lockdown and isolation, but feeling like I'd really gotten screwed over by having a book released in that dead week between Christmas and New Years when no one—not even people who were stuck at home with literally nothing else to do—was paying attention. I had a Zoom event or two and of course posted the shit out of it, but I remember spending so much time just stewing in my misfortune.

But I probably would have been doing that no matter what. Before that, I'd published a cookbook and joke book about dads and a cute little witchcraft guide for teens, but this was a collection of personal essays, and in my mind it was supposed to be my Big Adult Book. I thought this was my ticket to people taking my seriously as a writer, an expectation which could never be reached no matter the release date or the sales or the coverage. I really thought this was a great book (or the best I could write at the time), but I also definitely thought I should publish a book because that's what writers do. I wanted it to legitimize me, and how could it ever do that? I think it's really easy to create goals for a book that you have absolutely no control over, which means that when something inevitably doesn't happen the way you thought, you feel both disappointed and helpless. I'm toying around with an idea for another book in a Google Doc, but I realize often when I open the doc it's because I think at this point in my career I should publish another book. I don't know if I'll ever totally get rid of that thought, but ideally, if I ever publish again, it'll be because I have something to say that this format is the best for, not because I just think I should.

Jaya Saxena is the author of The Book of Lost Recipes (Page Street 2016) and Crystal Clear (Quirk, 2020).

Rumaan

Handing the rough material that might someday be a book to my agent or editor is a strange experience. People who are not me suddenly have access to something that has previously existed only inside my brain. When I hear my agent or editor mention characters by name, I think, oh, you know these people too? Weird.

I think what I find deranging about publishing a book is essentially this, that my private delusion is made public. And the impulse to want the book to find readers even as I want to shy away from them, begging them not to look. And the knowledge that the thing once held only in my mind was perfect, because it was pure potential, not flawed, as everything real must be.

I have got better, over the course of four books, at managing the vulnerable period when a book first appears, or I pretend (I’m good at self-deception). I’ve cobbled together advice heard from my editors and agent and other writers older and more seasoned and better than I am; maybe the book that matters most is the one that exists only in the mind, the one that’s pure potential, the next one. This makes it easier for me to sit in conference rooms discussing the marketing plan or on panels chatting about the book itself; no one else knows about the book I really care about, the next one, which only belongs to me.

Rumaan Alam is the author of Rich and Pretty (Ecco, 2016), That Kind of Mother (Ecco, 2018), Leave the World Behind (Ecco, 2020), and Entitlement (Riverhead, 2024).

Danny

Usually whenever I make an effort to have no desires or expectations around something, it's because my expectations are high and I'm trying to prevent disappointment. It usually doesn't work, which is not to say that feeling disappointment is inevitable, just that trying not to have expectations doesn't work for me.

I think my first book came out in 2014. Since then I've usually published a book every other year or so. One of them was just a collection of columns I'd done as part of my contract as an advice column, so I didn't have many strong feelings about it. That felt pretty easy. One of them was a memoir that came out kind of right in the middle of becoming publicly estranged from my family over my brother's pedophilia that required a hasty rewrite of the ending when the book was supposed to be going to press, which felt pretty bad.

My first book was a collection of goofy jokes about literature and sold better than any other book I've written since. It was the sort of book you could get a relative you didn't know especially well who had an English literature degree, so it did well on the gift market. I believe my advance was $55K (back in 2012) and I still get a small royalties check (anywhere from $50 to $200) once a year or so. I was in my mid-20s, the book had been relatively easy to write, and going to readings was fun. I got good advice about remembering to be enthusiastic about any audience that turned out to a reading, big or small, because over the course of a hopefully long career those numbers would go up and down for any number of reasons, and that's served me well. If I have a reading and only a few people attend, I feel disappointed for a moment, and then I set it aside and focus on the people who came.

My next book is coming out in October and I only have two events scheduled. It's nice not to overschedule a book tour. The events don't usually move the needle much on sales so unless it sounds really fun and you have a lot of free time, you're probably better off only going to as many events as you practically can while still enjoying yourself, not stressing out, and not spending your own money on travel. Of course if your publisher will pay for your travel that's another story.

And of course there's a whiff of coping mechanism to "it's nice not to be overscheduled," isn't there? The implication being that one is otherwise so successfully busy that downsizing comes as a relief. When of course if I were to be overscheduled because the book was such a runaway hit, I would cheerfully abandon the "this little house is just the right size for me!" approach and plaster my social media with whistle-stop tour graphics. I would love to be overbooked. "Him again? He's everywhere!"

I do want things. I want the books to be good, I want the readings to be well-attended, I want my readers to be conscientious and intelligent and tasteful. I don't want to feel contempt for myself or for others. I sometimes find publication day/week anxiogenic, but rarely deranging.

For this book, since it's a novella, I got an advance of $20K and a pretty short turnaround time. I was happy with the money and the schedule, since it's sort of a one-off Christmas special. I do hope that it will do well, because I would like to continue the Women's Hotel series, if at all possible. But I don't know if that will be possible.

I won't include any links, but I'm happy to have gotten to speak about this a bit. I do feel that it's time for a change, for me. I hope to be able to keep writing books but I don't know how much more of a newsletter hustle I have left in me. I'm starting a new day job for the first time in twelve years next month. Full time and everything. I'm excited about it, especially after a few years of trying very hard to find full-time work and not being able to do so, but of course it also brings with it a sense of change and of loss.

For whatever it's worth, every marketing person I've ever worked with has been pretty nice, at least in my recollection.

Daniel Lavery is the author of Texts from Jane Eyre (Holt 2014), The Merry Spinster (Holt 2018), Something That May Shock and Discredit You (Atria 2020), and Women's Hotel (HarperVia 2024).

Larissa

My first book, Fantasian, came out in 2016. It was a novella with a very small art publisher—Badlands Unlimited—that is now defunct. It was, honestly, a really fun and carefree experience, perhaps because I was 23 years old and Badlands was an art publisher, and the book emerged within the landscape of art books and erotic writing, a venue that, unlike traditional publishing, felt playful and light. There was basically nothing commercial about the experience and the book was minimally reviewed. Because physical copies are so hard to find (please don't buy it for $70), the book has a bit of a cult-classic status about it now. Typing all this makes me miss that era. I love weird books with small publishers!

My second book, Pop Song, was an essay collection that came out in May 2021. It felt like something I had been pushing myself to do for years—my first full-length book, with an indie but "traditional" publishing experience, at Catapult. It was really hard!! Having virtual events for the launch and tour absolutely wrecked me—it was so hard to be cut off from in-person literary community and not have a sense that people were excited about, or interested in, reading this book. I think Pop Song being nonfiction also contributed to the difficulty of the experience—I didn't know not to read reviews, and though most of them were exceedingly lovely, the bad ones—which of course, the book being nonfiction, feel so personal!—still play in my head on repeat. I still have a little trouble distinguishing the book from the trauma of its birth, lol, and I do feel very different from the person I was when I wrote it (spring 2020). It's funny because, on paper, the book did really well! But it came out at a really difficult time in my life, and I don't think I was entirely prepared for that level of exposure. It's also probably worth mentioning that immediately as this book came out, I went straight into a low-res MFA for fiction. Lying is the best :)

My third book, Discipline, is coming out early next year (Jan 2026!) with Random House. It's my first time working with a Big 5, as they say, and I feel very supported by my publisher, though also a bit overwhelmed by the scale of operations at a bigger house. It's also my ~debut novel~, as they also say, so I'm mentally preparing myself for the experience of being read on a larger scale. I have always dreamed of publishing fiction, and I am very happy with (and proud of!) this book, and I'm hoping to take the middle way with this one. I want to engage meaningfully with people who are reading and expressing resonance with the text, and I will try to practice not grasping and non-attachment with everything else! In the last years I've become more devoutly Buddhist, which should, I think, help with this. But I'll let you know in January of next year, when I will probably not be feeling this way.

Larissa Pham is the author of Fantasian (Badlands Unlimited 2016), Pop Song (Catapult 2021), and Discipline (Random House 2026).

Andrew

I've published two books, a novel and a story collection. I have a new novel coming out in March 2026, so this is very much on my mind again. I'd say both of the two completed experiences were anomalous, if not for the fact that no one I know has had a publishing experience that didn't seem so. I sold the two books together in 2017-- a full novel and an incomplete, fairly ramshackle batch of stories-- on my agent's advice that if I ever wanted to publish a story collection, this was my best chance. (The wisdom of this has been borne out in recent years by accomplished writers I know not being able to find homes for story collections.) Since the stories were published second, I ended up with plenty of time to add some good ones and take out the more apprentice-y stuff. If someone thinks you might be able to sell a story collection, DO IT.

I sold the books to my first choice of publisher, and had visions of glory. The editorial process for the novel was intense but gratifying; the book shed over 25,000 words and became, I think, its best self, or at least a much better self. The book was due to be published in July. In November, my editor resigned amidst accusations of sexual impropriety. The cover was half-designed, the publicity plan nascent, the foreign rights unsold. I was assigned another editor, who I liked very much, but the sense of being damaged goods was palpable. The photographer whose image we wanted to use for the cover refused us the rights to it. The book's publicist grew distant, then quit the day before the book came out. It wasn't reviewed early in Publishers Weekly. Etc.

For better or worse (better, in the end, probably), I did a lot advocating for the book myself, getting it into the hands of everyone I'd ever worked with in the publication world, setting up events in places where I knew people, even if there wasn't a budget for travel. I did my best and braced for publication. The first "review" was in the Washington Post, which I sadly don't subscribe to anymore; the gist, in a column from their longtime regular critic, was tl;dr, since it was just another book about a lazy, drunk male writer who doesn't do anything. A week later, Molly Young, who seemed to have, in contrast, read it to the end, gave it a rave in the Times Book Review, and suddenly the book had a life. It was still the weird, ugly little book it had always been, but now it got a line in Vogue and was in a pile of books on the set of Good Morning America. Ann Patchett mentioned it on PBS. It lived to reach a respectable, round number of sales, after which I stopped asking.

The shorter story of the story collection is that it came out in July 2020, when the last thing on anyone's mind (correctly) was a story collection about aging millennials etc. My editor was laid off before the book came out in the chaos of the early pandemic economy. I got my first lengthy pan on publication day, which was annoying, but also pretty interesting. I was too afraid to ask how many copies it sold, but I eventually got an email asking what I wanted done with the remainders, so I assume the number wasn't great. And yet! The book has had a life, maybe a more interesting, bohemian kind of life than the novel. Writers I admire will tell me they taught a story from it. MFA students, the main audience for stories at this point, seem to dig it. I'm at least as proud of its place in the world as I am of the more conventionally successful book.

The lesson I've tried to take from all of this is not to have too many expectations about outcomes, but also to do everything within my own power to give my books the chance to find readers. I try to say yes to every reasonable request to do a reading, interlocute a talk, or speak about my work, even if there isn't obvious financial or reputational gain. I try not to be cynical about "the business," in part by superstitiously trying to avoid the details of who gets paid what, who got which prestigious thing. Of course, these things are unavoidable-- I said "try." To me the only reasonable goal is to do well enough that you can afford to keep writing and publishing, which is far from a guarantee. I advise listening to a lot of Bruce Springsteen (circa 78-87) to find the will to go on.

Andrew Martin is the author of Early Work: A Novel (FSG, 2018), and Cool For America: Stories (FSG, 2020).

Katie

The highest high I've experienced as a writer was the first time I ever published anything (an essay on The Hairpin, RIP), and my most successful book (so far...) was my first. Sometimes that's disappointing to think about — I think I've gotten much better since then! — but I think it's also pretty normal. There's extra attention and effort around a debut, and it's a new experience, so it's more exciting for everyone. If you expect that kind of buzz for every book, you'll probably be disappointed. That's okay — and when you have a book come out, there's always some letdown or another — but I think it's served me to keep my expectations relatively modest, and hold on to my day job(s). My agent was very pragmatic from the start, which also helped. And I feel lucky that I read Bird by Bird early enough for it to be formative for me: You have to get the most joy from writing itself because nothing else is guaranteed, and publishing rarely feels as uncomplicatedly great as you might imagine. Obviously, I hope I get to keep doing it anyway. I like writing more now than I did 10 years ago, and I want my work to be read. I'm always rushing to finish a project and always reminding myself not to be. This is the fun part.

Katie Heaney is the author of Never Have I Ever (Grand Central, 2014), Dear Emma (Grand Central, 2016), Public Relations (with Arianna Rebolini, Grand Central, 2017), Would You Rather? (Ballantine, 2018), Girl Crushed (Knopf, 2020) and The Year I Stopped Trying (Ember, 2024).

Isle

If you’re lucky, writing a book is an insulated activity. When I’m in the early stages of drafting, no one cares what I’m writing; I’m free to play and explore on the page. But when I publish a book, I’m forced to confront two things. First, no one cares, because there are simply too many books. This isn’t the worst thing in the world—it’s good to stay humble. And second, once the book is published, I’ve lost the greatest pleasure of obscurity: the ability to play and explore. It demands a kind of grief, or acceptance, to put out a book, knowing there’s nothing more you can do for it, especially not on the page. My advice is to see the book as a moment in time, an expression of a self in amber, rather than a reflection of the person putting it into the world. Because if you see the published book as a reflection of yourself, then every bad review or missed list will feel like a sign of a personal flaw (at least it did for me). More importantly, though, is to return to the obscurity of a blank page as soon as you can. Getting under a new book is the best way to get over a published one.

Isle McElroy is the author of The Atmospherians (Atria, 2021) and People Collide (HarperVia 2023).

1 While putting this together, I noticed that several respondents reproduced language of my original email soliciting their participation. While I think everything is clear and stands alone, here is some additional context: I said I wanted “thoughts on the potentially emotionally/mentally deranging experience of having a book come out” and wondered whether, for them, the experience got better or worse over time, or didn’t change at all.

2 Prostitute Laundry’s number does not include sales through Serpent’s Tail (which have been exceedingly modest as best as I can tell) or EmilyBooks (R.I.P.)

3 Back in 2006, Publisher’s Weekly suggested that “the average book in America sells about 500 copies.”

4 This doesn’t mean I will never work with another publisher again! On the contrary, I would prefer it for most (but not all) of the book-length manuscripts I have in mind. But the self-publishing first, then traditional publishing sequence was immensely valuable and I wouldn’t want it to have happened any other way.

5 (This is not a complete list and no slight is intended to the stores I left out, except for one, who knows who they are.)

6 What really matters most isn’t crowd size but crowd attitude. I’ve done dozens of readings over the years and my favorite audience ever is still Charlie Jane Anders’s Writers with Drinks, back in 2015. Of course the crowd was getting sauced but I don’t care if they’d been gassed with nitrous oxide; they were a blast. I also liked that afterward a guy came up behind me and held me so confidently that I just went with it because I thought he was Sam. I know I’m not supposed to like that he did that, but I do. I guess that’s a newsletter for another time.

7 I think this (book coverage, criticism, reviews) is a topic for another time, too, because I keep trying to write more but feeling stymied, and my conclusion is that it needs more space than I’m currently willing to give it.

8 A lot of that might have been my publicist, Cat—thank you, Cat!